+4°C - from Folgefonna to The North Sea‘, Sleppet, Greig07, Utlima, Oslo, Norway, 2007

31 August 2007

Møllergata 13, Sleppet was part of the Ultima festival in Oslo.

Artists: Chris Watson, Natasha Barrett, Steve Roden, Bjarne Kvinnsland, Marc Behrens and Jana Winderen, curator: Jørgen Larsson.

The project is supported and organised by Grieg07 and curated by Jørgen Larsson. Thanks also to Vederlagsfondet, Notam Asbjørn Blokkum Flø and Cato Langnes and Folgefonni Breførarlag. The work with the installation was supported by NBK, Norske billedkunstnere.

http://www.grieg07.no

https://notam.no

https://www.norskebilledkunstnere.no

The installation +4°C - from Folgefonna to The North Sea

Text for the exhibition catalogue

The soundscape of the Hardanger Fjord is as beautiful to listen to under water as its landscape is to behold above. The fjord is full of babbling fish: haddock feeding, cod spawning, snails slowly pulling themselves across rocks, and noises you can barely hear, let alone discover from where they originate. I am listening on a boat using headphones, with the hydrophones 25 metres down.

My installation for the Sleppet project, +4°C - From the Folgefonna Glacier to the North Sea, follows the sound of Norway's third largest glacier from the slushy ice on its surface, through crevasses and 25 meters into the blue ice below. I followed the melt water down through valleys towards Rosendal and on to the Hardanger Fjord; the recording ended at Langevåg near Bømlo where the Hardanger Fjord meets the North Sea.

My reason for choosing the Hardanger Fjord and the Folgefonna glacier is because this is some of the most beautiful landscape we have in Norway, and there is a connection with Grieg and the way I remember Grieg as I grew up in Norway. I relate to Grieg through my childhood memories of his music, not from my adult experience of it. I wanted to grasp the overwhelming beauty of the landscape in the area around Folgefonna, Rosendal and the Hardanger Fjord, and my impressions of paintings from this region dating from the time of Grieg.

Just as Grieg went around collecting folk tunes in Hardanger, I have collected the sounds of running water and melting ice with my instrument, the hydrophone, in the same area. A hydrophone is a microphone for recording sounds below water, and can also be used in ice, sand and earth.

I have been on several trips to the Folgefonna glacier. From the local glacier guides at Folgefonni Breførerlag I have heard numerous myths, stories and scientific facts about the glacier and its origins. I have walked along the streams and rivers that run from the edge of the glacier, and along the valleys and the extremely steep mountainsides; I have observed the glacier as an organic being, melting and changing its shape and expression each time I have visited.

The melting produces a characteristic sound. At the same time the changing nature of water and its properties are conceptually rich and powerfully elemental. There is something ominous about the melting, while at the same time the sound is very delicate and beautiful.

I wanted to find sounds that were not necessarily accessible or familiar to us; sounds that people may never have heard, or even noticed. Snails, for instance, make sounds eating seaweed, cod communicate with sound, the various layers of ice have their own complement of sounds, and the sound of a stream can vary immensely over just a short distance. When I use hydrophones I am fascinated by the mystic process of fishing for sounds. This is field recording, but field recording blind. I cannot be certain what is making the sounds I hear when the microphones are 25 metres below the surface (even though I can recognize from experience quite a few different fish). Each time I go out recording I am always pleasantly surprised - I will always remember the first wild cod I recorded at Gjermundshavn in the spring, or the heron that sat close to me in pitch darkness at Langevåg wile I was listening to the haddock grunting below the surface.

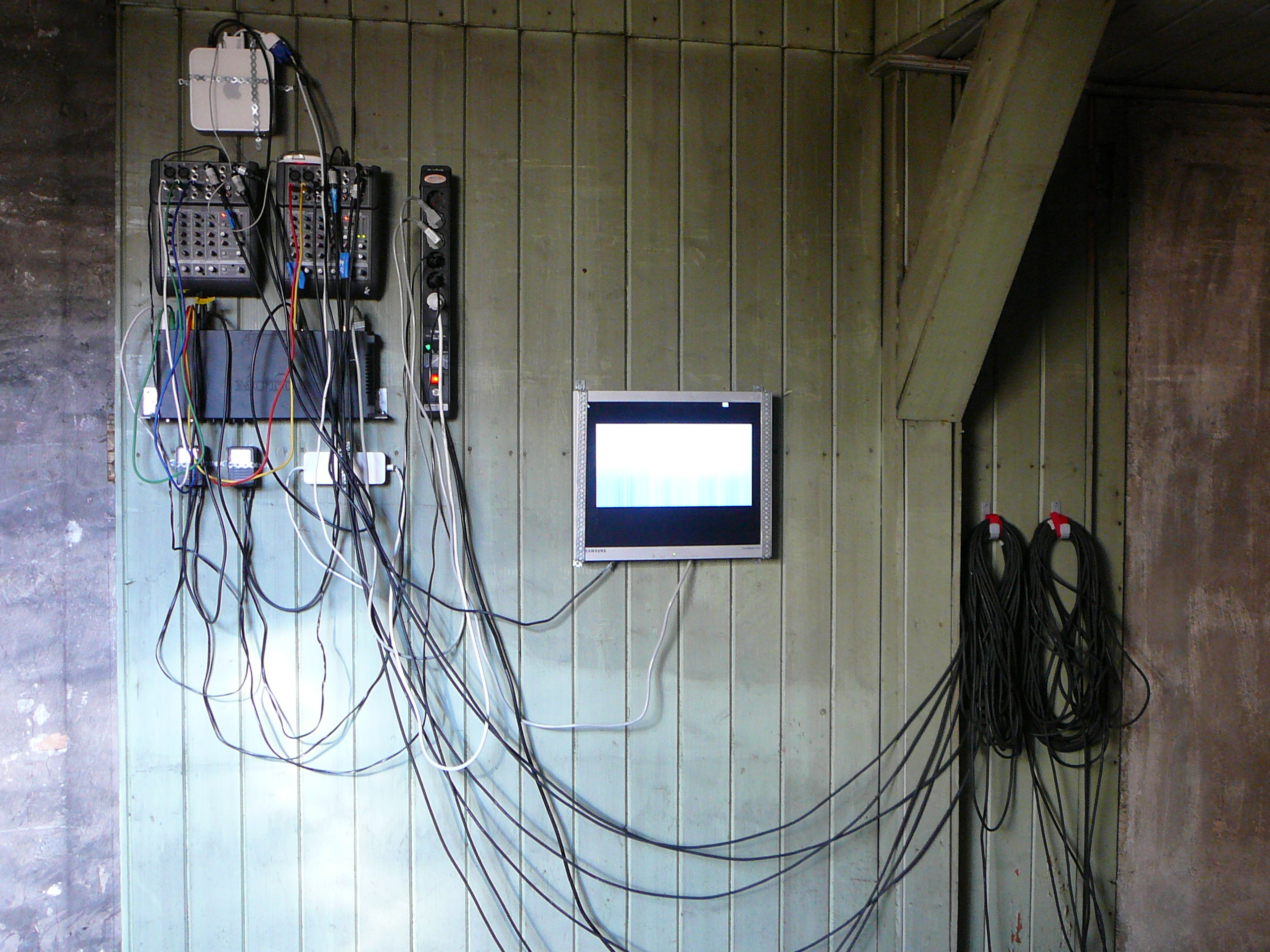

During the last two years I have travelled a great deal - to Canada, Greenland, Thailand, many places in Europe and in Norway, and everywhere I have been I have recorded sounds with hydrophones, in rivers, canals, glaciers and oceans. When I record sounds out in the wild I always listen with 2 or 4 hydrophones and microphones for interesting compositions within the sounds themselves. In the editing process I do little with the sounds other than emphasize what I find interesting in the sounds themselves. I use my own ears to judge what is interesting. In Bergen the sounds will be installed on ten loudspeakers in two rooms - two rooms in the process of decay; but I do not want to change the rooms too much, just leave them as they are, beautiful in their state of decay.

Even though standing close to a waterfall can be a noisy and stressful experience over a long period, the sound of an engine is harder to tackle because of the endless monotony it represents. Waterfalls, rivers, streams and waves change all the time. Therefore we perceive them as organic, and something we like to rest our ears on. Water sounds are very special to human beings. We consist of 60-80% water and water sounds are among the first we hear. We are influenced by the level and balance of water in nature, where it makes up 70% of the earth's surface - we know so little about soundscapes and aural communication beneath the surface.